Dismiss the health of students and students will miss school: amend the pupil attendance policy in California

April 30, 2020

School. Study. Sleep. Eat. Repeat. Hardwired to perform well in school, students can hardly catch a break as they experience prolonged periods of stress and neglect their health to achieve the outstanding academic results they desire. Aiming to reform the way that California’s school districts support the wellbeing of their students, Senator Portantino introduced a bill in early January of this year that would amend the pupil attendance policy to excuse mental or behavioral related absences for students missing school in order to recover or receive treatment. Though some districts have independently acted to support these students by providing on-campus psychologists and special programs, school districts are not currently required to support students with mental and behavioral health issues.

“By including mental and behavioral health to the absence policy in California, parents will have their eyes opened to how debilitating poor mental health can be and how children, especially stressed teenagers, need time to escape that stress and relax,” said Skye Masaitis (12), vice president of Bring Change to Mind club.

Providing inadequate support, sends out the wrong message to students: academic success outranks mental and behavioral health as a priority. Schools should not encourage students to jeopardize their health by invalidating their illness or disorders and contributing to stigmas.

“At MHHS, our goal is to support all students as much as possible when it comes to truancies. The same goes for students with underlying mental health or behavioral health issues. We have a pretty amazing support team that includes our counselors, school psychologists, and a social worker (me). Our support team works together to support the student and family as much as possible during these times in hopes of finding a way to encourage our students’ attendance,” said Ms. Diaz, the social worker at MHHS.

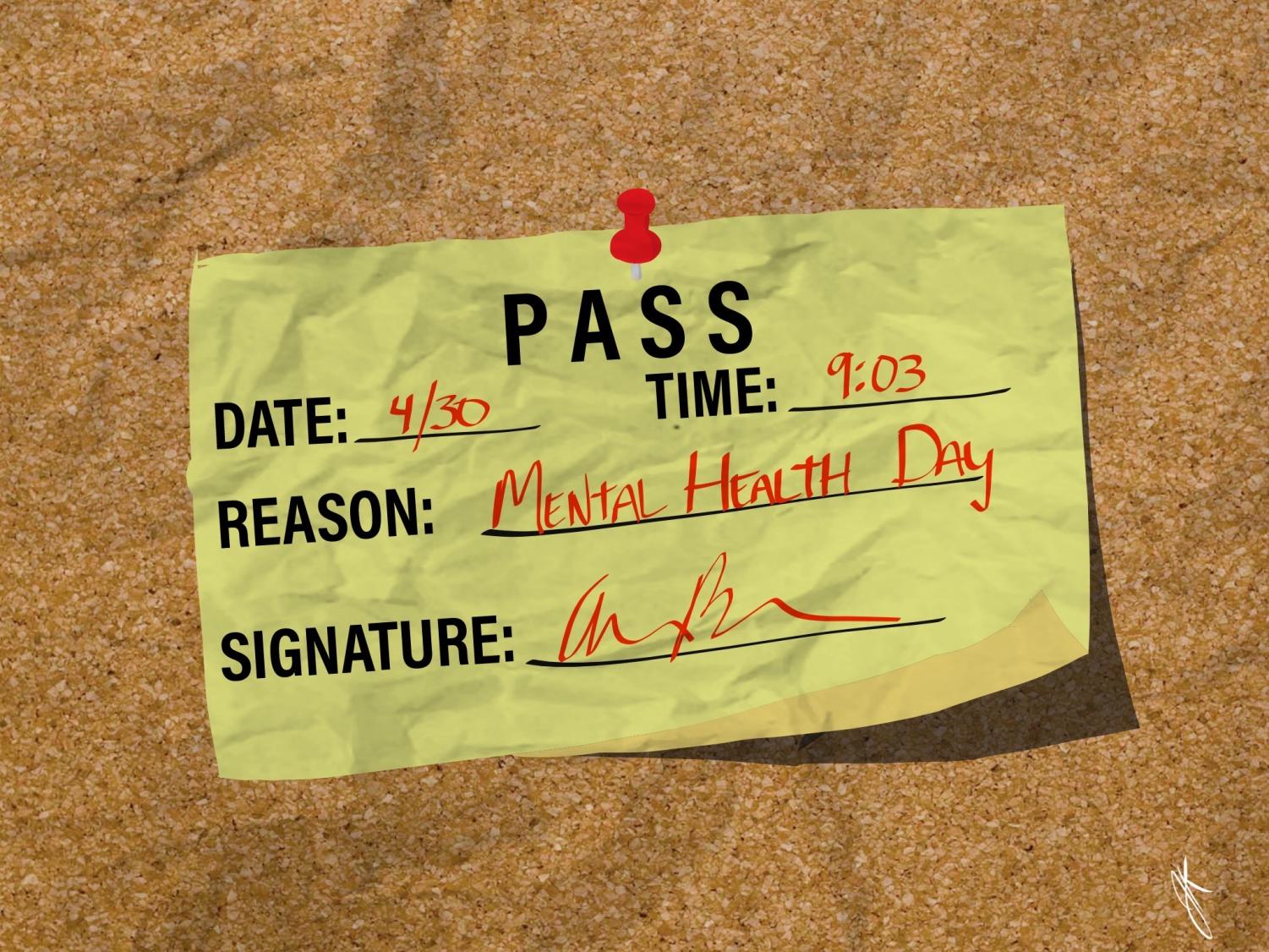

An ongoing effort to destigmatize mental and behavioral illnesses, as research continues to improve our understanding, has led to the popular trend of taking a “mental health day”—missing a day of school to catch up on neglected self-care or basic needs like sleep without consulting a doctor.

“There are adults that also use that term, but for students, I think it’s different because if they don’t have the right coping strategies and are going through a crisis, we would rather have them on campus to provide support and make sure they are in a safe place. I’d rather have the students be at school where they might need a break for ten minutes or a class period instead of a whole day. It doesn’t always have to be a therapy session. Just communicate with me,” said Mr. Lozano, a school psychologist at MHHS.

At San Marcos Unified School District, we are fortunate to have adequate teams of counselors that work hard to equip students with the necessary resources and opportunities to overcome adversity or a crisis, but this does not ring true for other districts that care more about losing funds from a student’s absence and don’t bother addressing the underlying issues.

“Honestly, some students might abuse this policy if given the chance, meaning that a set number of excused mental health days would need to be placed. However, that limit would then impede on students who do need a lot of time to work on their mental health,” Masaitis said.

So while many people are in support of changing California’s approach of ensuring the mental and behavioral wellbeing of students, many are still unsure of what this translates to for students and districts. The hearing for SB-849 was postponed by the Committee on Education on March 25 in order to help districts transition into distance learning, but one thing certain: we should not postpone our young students’ attempts to find balance between being productive citizens and taking their health seriously.